FILM:

The Reluctant Killer and the Rogue Agent: Timothy Dalton's Darker Shade of Bond

Between 1986 and 1989, the James Bond franchise took an entirely different direction with both ‘The Living Daylights’ and ‘Licence to Kill’ bringing a darker, more human edge to the character. Sadly, short lived due to to legal issues putting the Bond series on hiatus for six years, but these two films remain a percussor to both the Brosnan and Craig era’s taking Bond well into the 21st Century.

By 1986, the James Bond franchise was fast approaching it’s 25th anniversary and had been portrayed by Roger Moore for the last thirteen years which led to an increasing desire to either reboot or drastically change the tone and pace of the films that had been a blockbusting success for the last quarter of a century.

Sandwiched between the increasingly fantastical escapades of Roger Moore and the gadget-laden revival spearheaded by Pierce Brosnan, Timothy Dalton's brief, two-film tenure often stands apart. His portrayal in The Living Daylights (1987) and Licence to Kill (1989) offered a stark, often brutal departure, grounding Bond in a grittier reality and deliberately exploring themes of loss, anger, revenge, and the grim nature of violence – elements largely subdued in his predecessors and later refined by Daniel Craig.

Following Roger Moore's departure after A View to a Kill (1985), the Bond producers sought a distinct change of pace. Moore's Bond, while immensely popular, had become synonymous with raised-eyebrow humour, outlandish plots, and a certain suave detachment from the often-lethal consequences of his actions. Timothy Dalton, a classically trained actor with a background in Shakespeare, consciously aimed to strip away the accumulated layers of parody and return to the roots of Ian Fleming's creation: a colder, more complex, and conflicted secret agent. He reportedly revisited Fleming's novels, identifying a character burdened by his profession, a reluctant killer rather than a gleeful, sometimes camp, adventurer.

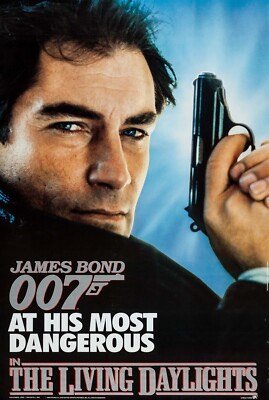

The Living Daylights served as Dalton's introduction and represented a transitional phase. While retaining familiar Bond elements – exotic locations, impressive stunts, a Q-branch filled with gadgets, and a central romantic entanglement – the film immediately establishes a different tone. Dalton's Bond is introduced not with a casual quip, but during a tense training exercise resulting in the death of another “00” agent. His defining moment involves refusing a direct order to assassinate KGB General Pushkin, instead using his expertise to fake an assassination, sensing something amiss. When he is faced with the supposed sniper Kara Milovy, he deliberately shoots the rifle from her hands rather than killing her, stating, "Stuff my orders! ... Tell M what you want. If he fires me, I'll thank him for it." This reveals a Bond operating on a personal moral compass, exhibiting a weariness with the bluntness of his licence to kill, a stark contrast to Moore's often casual dispatching of foes. While loss isn't a central theme of The Living Daylights, the film subtly hints at the cost of the job – the constant vigilance, the inherent danger, the potential for being manipulated. Bond is angry, churlish, but it's controlled, professional fury directed at betrayal and incompetence within the intelligence community. Violence is depicted as a necessary, often messy, tool of the trade rather than a stylish flourish. Compared to some of Moore’s entries, the violence feels more impactful and less cartoonish.

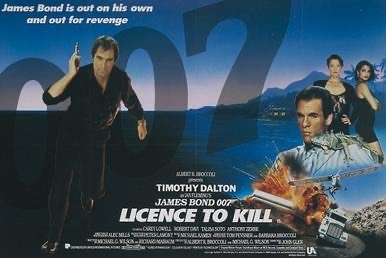

However, it is in Licence to Kill that the potential darkness inherent in Dalton's interpretation is unleashed, and, as a result, pushed the boundaries of the franchise. This film stands as an anomaly in the pre-Craig era, stripping Bond of his official sanction and plunging him into a deeply personal quest. The catalyst is the brutal attack on his CIA friend Felix Leiter and the murder of Leiter's new wife, Della, orchestrated by the sadistic drug lord Franz Sanchez. This act transforms Bond. The loss is immediate, visceral, and deeply personal. Unlike the more abstract losses or professional setbacks in previous films (with the notable exception of his wife’s death (interestingly, and surely by no accident, referenced in Licence to Kill) in On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1969), the aftermath of which was never explored, this loss ignites a raw, consuming anger in Dalton's Bond.

His confrontation with M, where he resigns from MI6 after being ordered to drop his pursuit of Sanchez, crackles with barely suppressed fury. "I owe it to Leiter, he’s put his life on the line for me many times", Bond grits out. The theme of revenge becomes the film's driving force. Bond operates not as a secret agent, but as a rogue element, systematically dismantling Sanchez's operation from the inside using manipulation, deception, and calculated acts of violence. His methods are ruthless, bordering on cruel, orchestrating betrayals within Sanchez's ranks, and ultimately immolating Sanchez himself with the lighter Felix gave him.

The violence in Licence to Kill is significantly escalated, both in frequency and graphic depiction, reflecting Bond's enraged state. The decompression chamber murder, Leiter's mauling by a shark ("He disagreed with something that ate him"), the demise of a henchman in an industrial shredder, and the explosive, fiery climax are far more brutal than anything seen in the Moore era and arguably surpass much of the Connery era's violence in sheer visceral impact. This heightened violence directly mirrors Bond's internal state – his rage makes his actions harsher, less clean, and driven by a desire to inflict pain mirroring his own. It drew criticism at the time for being too dark and straying too far from the Bond formula, feeling more akin to the gritty action thrillers popular in the late eighties.

Comparing Dalton's Bond to his predecessors highlights the radical nature of his portrayal concerning these themes. Sean Connery's Bond was capable of cold brutality but his motivations were primarily professional, laced with a certain suave ruthlessness. Anger was rare, and personal revenge wasn't a driving factor. Lazenby's Bond experienced profound loss but didn't have the screen time to explore its consequences. Moore's Bond, particularly in his later films, existed in a world where violence often lacked weight, and personal loss or deep-seated anger were almost entirely absent from his characterisation. Dalton, therefore, reintroduced a psychological depth and emotional vulnerability tied directly to the grim realities of espionage and personal connection, unseen since glimpses in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service.

Looking forward, Dalton's portrayal, particularly in Licence to Kill, can be seen as a clear precursor to Daniel Craig's era. Craig's Bond is defined by loss, driven by anger and revenge, and operates in the 21st century world where violence is brutal, personal, and leaves scars, both physical and psychological. The raw emotion, the willingness to go rogue for personal reasons, and the exploration of the toll the "00" status takes on the man – these hallmarks of the Craig era find their roots in Dalton's interpretation. While Pierce Brosnan attempted to blend Dalton's edge with Moore's charm, his films generally shied away from the sustained darkness and personal vendetta that characterized Licence to Kill. Brosnan's Bond might express anger or mourn a loss, but it rarely consumed him or drove the narrative in the same obsessive way it did for Dalton in his second outing.

In conclusion, Timothy Dalton's James Bond was a deliberate and significant departure. The Living Daylights offered a more serious, reluctant agent, hinting at the burdens of the job. Licence to Kill plunged this interpretation into the crucible of personal loss, unleashing a Bond consumed by anger and driven by a brutal quest for revenge. The violence became harsher, reflecting his inner turmoil. While perhaps jarring for audiences accustomed to Roger Moore's lighter touch, Dalton's tenure explored the darker facets of the Bond character, grounding him in a more dangerous reality and examining the psychological consequences of his violent life. Though his run was short, Timothy Dalton provided a vital, grittier interpretation that challenged the established formula and, in retrospect, laid crucial groundwork for the emotionally complex, modern incarnation of James Bond. He demonstrated that beneath the tuxedo and the gadgets could beat the heart of a man capable of profound loss and driven by the most instinctive and natural of human emotions.

(C) 2025 Rob Taylor